Why it matters to go underground

Whereas colourful images come to our mind when we think about aboveground biodiversity of animals and plants, aspects of below-ground or soil biodiversity are more vague, or even mysterious. Standing on the land surface, we usually do not see life in the soil; and even here inside of the World Soil Museum the immense role the soil organisms play cannot easily be read from the monoliths on the walls. So why go underground?

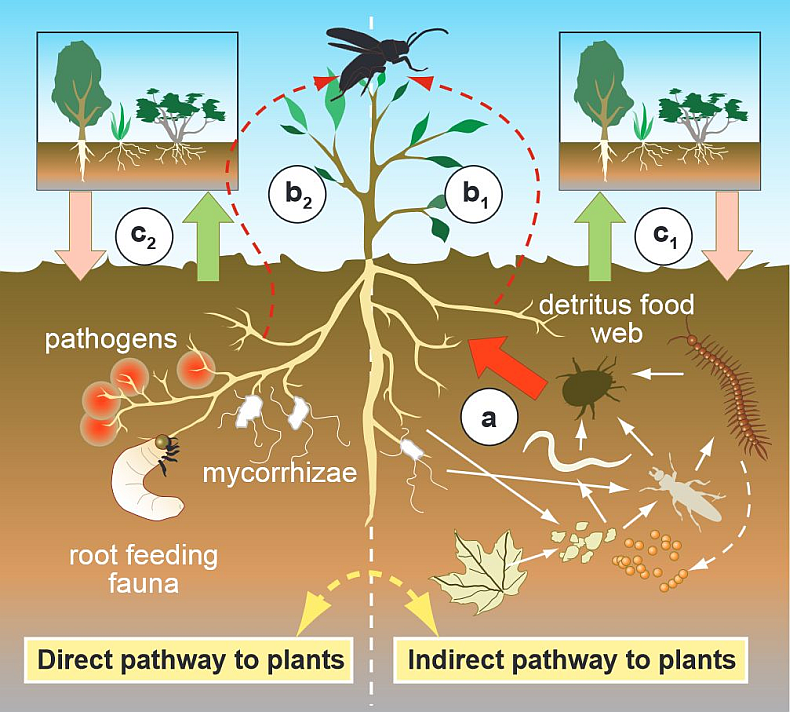

The answer is simple: What happens in the soil is important for the aboveground life, and vice versa. Or in other words: Most ecosystem processes and functions that occur within soil are driven by living organisms that, in turn, sustain life above ground. There is ample research in ecology on these aboveground-belowground linkages. An 8-year experiment, e.g., studied a wide range of above- and below-ground organisms and multitrophic interactions in a temperate grassland, and found that plant diversity has strong bottom-up effects on multitrophic interaction networks, with particularly strong effects on lower trophic levels (Scherber et al. 2010).

The diversity of soils – that you see on the walls all around you – could not be understood without the diversity of plants, animals and microbes that contributed to soil formation. Think of the living organisms that break down bare rock through chemical weathering, thus ‘kick-starting’ soil formation. Or think of the various types of vegetation and the effect of litter quality on soil chemical and physical processes. Another good example is the occurrence of mycorrhizal fungi in soil which can determine the presence or absence of certain plants.

On a larger scale, the correlation of soil and biodiversity can be observed spatially. For example, both natural and agricultural vegetation boundaries correspond closely to soil boundaries, even at continental and global scales (Young & Young, 2001). It is possible to show how typical soil forming invertebrates also follow these boundaries.

|